|

Today, the very fabric of our society depends on schools and our system of education for the imparting of knowledge to its people. This in turn enables the society to function. However, schools and the system of education are entwined together with tests, exams and grading. These tests, exams and grading, have become such a part of the education system and the function of schools, that it is difficult to imagine learning without them. For this site this creates a dilemma. On the one hand, we do not wish to abandon schools as a possible source of learning, but on the other, we wish to maintain that the pressure of tests, exams and grading are not necessary for learning to take place. Learning, as explained elsewhere in this site, is something each person must do themselves. It can and does happen anywhere, not just at schools. This site will endeavor to present 12 keys to learning which are derived from the great thinkers in learning and are intended to help ordinary people learn more efficiently and easily. However, if these keys are approached with the idea that they need to be combined within a system that is mired by grading, it is feared their usefulness will be severely hampered and perhaps they will be modified so much that they become unworkable. Many educators and psychologists have suggested that there may be no need for any grading in the actual learning process and that it is probably harmful to learning. What then could be a possible use of testing? Exams and tests. What is their purpose? Exams or tests have three important things that they contribute to learning.

How learning works.

We receive information in many forms and through many senses. Our brains are evolved to be particularly good at remembering things that we see or images and we are constantly taking in images and encoding them into a vast store. While this is our primary form of learning it is not the kind of leaning that we do in school. In school we use language. Language is a secondary code. It is not part of natural sounds that have their own meaning like the sound of footsteps or running water but a made up code that uses sound. Written language is yet another different code that uses verbal language as its base and translates it one for one into the images of writing. These two codes are much more difficult to bring to mind than the more natural sounds and images, that we are better adapted to encode, so we are not good at remembering them. But we can be a lot better than we are. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel tell us how encoding works when we are learning a skill as follows: "The

brain converts your perceptions into chemical and

electrical changes that form a mental representation

of patterns you've observed. This process of

converting sensory perceptions into meaningful

representations in the brain is not perfectly

understood. We call the process encoding, and we call

the new representations within the brain memory

traces. Think of notes jotted or sketched on a

scratchpad, our short-term memory." This

process is already very complicated and it is made far

more complicated by the two further layers of code when

converting writing. We can partly overcome this directly

linking images to concepts/ideas or the words written or

spoken that stand for those concepts and ideas. When we

do this with intention to make learning easier it is

sometimes called dual coding.

Consolidation is the process by which encoded memories go from working memory to a temporary memory record in storage. If the memory is recalled or used enough the memory becomes more permanent and is eventually stored in long term memory. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel also tell us how consolidation works as follows: "The process of strengthening these mental representations for long term memory is called consolidation. New learning is labile: its meaning is not fully formed and therefore is easily altered. [Memories when they are recalled are also labile.] In consolidation, the brain reorganizes and stabilizes the the memory traces. This may occur over several hours or longer [sleep may be required] and may involves deep processing of the new material, during which scientists believe that the brain replays or rehearses the learning, giving it meaning, filling in blank spots, and making connections to past experiences and to other knowledge already stored in long-term memory. Prior knowledge is a prerequisite for making sense of new learning, and forming those connections is an important task of consolidation." When a memory is retrieved from storage it goes back into storage different to how it came out. This is because when it is retrieved it becomes labile again, and a process called re-consolidation takes place. This process is essentially the same as consolidation just not occurring for the first time. As portrayed above consolidation has many different things going on but its main function is to link the new material to prior knowledge held in long term memory. This process is what is called elaboration and will be featured later below.

When we encode something into memory the default is that it starts to die immediately. Memories come in but they also leak out. Our brains discard memories not in order to make room for new material but mostly so we can find knowledge in the massive clutter. In other words we forget things that our brain perceives as unimportant, which it decides by taking note of how many times it is recalled.

There are many conditions that give a memory a much better chance of survival and most of these are covered on the page called contagion. But almost none of these conditions are sufficient by themselves, to ensure that the memory gets firmly embedded in long term memory. The most obvious of these conditions, memories laced with strong emotions and memories that we develop a strong interest in, are also conditions that ensure those memories will be recalled. It may well be that the only reason we are able to remember memories at all is because we have recalled them a many times already. If we do not recall a memory close to its initial encoding the chances are that we will never recall it.  WHY WE LEARN HAS THREE PARTS.

Elaboration creates and improves understanding. Elaboration in the study of memory has been said to be the unintuitive way in which memory seems to work where remembering more information seems to make memories more permanent and more easily recalled than simpler and smaller amounts of information. While it is true that this process does seem unintuitive at first glance it is perfectly intuitive once we realize why it works the way it does. More connections gives both meaning and proves cues to it in the real world In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain elaboration as follows: "Elaboration is the process of giving new material meaning by expressing it in your own words and connecting it with what you already know. The more you can explain about the way your new learning relates to your prior knowledge, the stronger your grasp of the new learning will be, and the more connections you create that will help you remember it later."

"Learning

always builds on a store of prior knowledge. We

interpret and remember events by building connections

to what we already know." It may do this because some of your prior knowledge is consonant with the new information and automatically links up with it where it is the same or similar. In this case the process is simply additive in thus the information is simply assimilated into all that prior knowledge. But sometimes your prior knowledge is dissonant with the new information. This may require that the brain overwrite that previous knowledge or modify it before the new information can be assimilated. Thus it is said to be accommodated. You also have some control over this process by thinking about how the new information might connect with your previous knowledge. Whichever way this happens the data goes from being just information to being understood or being knowledge, or information that you now know.

"...one

cannot apply what one knows in a practical manner if

one does not have anything to apply."

"The

act of trying to answer a question or attempting to

solve a problem rather than being presented with the

the information or the solution is known as

generation. [We are either generating new

knowledge or discovering our lack of knowledge.] Even if you're being

quizzed on material you're familiar with, the simple

act of filling in a blank..." [creates new

tentative knowledge that must be judged either by

means of feedback from others or by strict testing

under scientific constraints.]

"Mastery in any field, from cooking to chess to brain surgery is a gradual accretion of knowledge, concept understanding, judgment and skill. These are the fruits of variety in the practice of new skills, and of striving, reflection, and mental rehearsal. Memorizing facts is like stocking a construction site with supplies to put up a house. Building the house requires not only the knowledge of countless different fittings and materials but conceptual understanding, too, of aspects like load-bearing properties of a header or a roof truss system, or the principles of energy transfer and conservation that will keep the house warm but the roof deck cold so the owner doesn't call six months later with ice damp problems. Mastery requires both the possession of ready knowledge and the conceptual understanding of how to use it." Knowledge,

skill and understanding. If we can borrow

from this house analogy. If memories (knowledge)

are the materials compiled for the house to built out

of, then high performance (skills)

are the tools we use to build the house, and

understanding (mastery)

is how it all fits together to make a good house.

Understanding is the connections and creation is

forging new connections. Practice of elaboration. When we consciously use activities designed to increase the likelihood of elaboration taking place there are two possible outcomes.

USES FOR LEARNERS. There are many things one can do to increase the possibility of elaboration. Here are a few.

USES

FOR TEACHERS. How can teachers present

material to be learned in such a way as to force

learners to elaborate more while learning and

studying.

USES FOR EXPERTS. Creative elaboration. A very nice example of how an expert might make use of elaboration is given in the book "Make it Stick". In the text they call it refection but reflection can be many things including retrieval and elaboration. This is a neurosurgeon called Ebersold reflecting on personal experience: "A lot of times something would come up in surgery that I had difficulty with, and what could I do, for example, to improve the way suturing went. How can I take a bigger bite with my needle or a smaller bite, or should the stitches be closer together? What if I modified it this way or that way? Then the next day back, I'd try that and see if it worked better. Or even if it wasn't the next day, at least I've thought through this and in doing so I've revisited things I learned from lectures or from watching others performing surgery but also I've complemented that by adding something of my own to it that I missed during the teaching process." [Or was never there.] This is a good example of how creativity emerges from elaboration. It also might have been a good idea for Mr Ebersold to have written down some of what he came up with, especially if it was likely that he would not get to try it out the next day. He also could have made some rough drawings of the new procedure. Visual elaboration. Our brains are much better at remembering images than they are at remembering words. This not only means we can remember words better by associating (linking) them with images that represent them but they also can provide a kind of scaffolding on which to hang knowledge. By associating images with the words we are reading we can elaborate the information we are taking in not only making it much more understandable but also much easier to remember. Each image is both a visualization of the process and an example of the process. Each an every image can be a cue to evoke recall of the knowledge. In the book "Make it Stick" they explain it as follows: "A powerful form of elaboration is to discover a metaphor or visual image for the new material. For example to better grasp the principals of angular momentum in physics, visualize how a figure skater's rotation speeds up as her arms are drawn into into her body. When you study the principles of heat transfer, you may understand conduction better if you imagine warming you hands around a hot cup of cocoa. For radiation, visualize how the sun pools in the den on a wintry day. For convection think of the life-saving blast of A/C, as your uncle squires you through his favorite back alley haunts of Atlanta."  Also in "Make it Stick" they give an example of this from medical student Michael Young who says: "'When

I read that dopamine is released from the ventral

tegmental area, it didn't mean a lot to me.' The

idea is not to let the words just 'slide through

your brain.' To get meaning from the dopamine

statement, he dug deeper, identified the structure

within the brain and examined images of it,

capturing the idea in his mind's eye. 'Just having

that kind of visualization of what it looks like and

where it is [in the anatomy] really helps me

remember it'"

In order

to understand about recall practice it is first

necessary to understand how memory and recall work

together to provide us with optimal information that

is easily accessible. There are a number of features

of memory and recall to be considered.  Forgetting is one such feature which has an important function in being able to recall. Every time we forget something we make our minds less cluttered and thus make the recall of information not forgotten easier to be recalled. Although there are many ways the brain makes information easy to recall the simplest way is to recall it many times.  If retrieving a memory once improves memory a lot next time we try to recall it why not retrieve it many times? The answer is yes but not all a once and rereading and rehearing are not the same as retrieval. The usual way people try to activate recall is to rehear the information or to reread it. In other words we try to improve our recall by studying. But this has been shown by recent scientific studies to be ineffectual.

Drilling,

the idea we can pound information into our heads by

force of will. This has long been our most

usual method of preparing to recall some information.

Saying, information over and over, reading it over and

over or hearing it over and over are our go to

methods. But scientific experiments as recounted the

book

"Make it Stick" tell a different story. The

authors Brown, Roediger and McDaniel have the

following to say: "Rereading text and massed practice of a skill or new knowledge are by far the preferred study strategies of all stripes, but they are also among the least productive. By massed practice we mean the single minded, rapid fire repetition of something you are trying to burn into memory, the 'practice-practice-practice' of conventional wisdom. Cramming for exams is an example. Rereading and massed practice give rise to feelings of fluency that are taken to be signs of mastery, but for true mastery or durability these strategies are largely a waste of time."

"In 1978, researchers found that massed studying (cramming) leads to higher scores on an immediate test but results in faster forgetting compared to practicing retrieval. In a second test two days after an initial test, the crammers had forgotten 50 percent of what they had been able to recall on the initial test, while those who had spent the same period practicing retrieval instead of studying had forgotten only 13 percent of the information recalled initially."

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE (ALSO KNOWN AS THE TESTING EFFECT).

"Retrieval practice - recalling facts or concepts or events from memory - is a more effective learning strategy than review by rereading. Flashcards are a simple example. Retrieval strengthens the memory and interrupts forgetting. A single simple quiz after reading a text or hearing a lecture produces better learning and remembering than rereading the text or reviewing lecture notes." "The act of retrieving learning from memory has two profound benefits. One, it tells you what you know and don't know, and therefore where to focus further study to improve the areas where you are weak. Two, recalling what you have learned causes you brain to reconsolidate the memory, which strengthens its connections to what you already know and makes it easier for you to recall in the future. In effect, retrieval - testing - interrupts forgetting.

Studying retrieval practice in the wild. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel recount many studies performed in exacting experimental conditions that show the testing effect which they have renamed retrieval practice greatly improves long term memory of that subject matter that is tested. However, they also ran some tests in the real word in a school. They approached the principal of a middle school in Columbia. This principal Roger Camberlain had some concerns as he saw memory as as mere unthinking regurgitation and was more interested in application, analysis and synthesis as well as varied instructional methods he feared would be disrupted. But he left it up to his teachers whether they would take part in the study. A sixth grade social studies teacher, Patrice Bain was eager to give it a try. The study had to be performed in the least intrusive way that was possible so that the principal's concerns were were dealt with. Here is what happened: "The only difference in the class would be the introduction of occasional short quizzes. The study would run for three semesters (a year and a half), through several chapters of the social studies text book, covering topics such as ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and China." The quizzes took only a few minutes of classroom time. After the teacher stepped out of the room, Argarwal [the research assistant] projected a series of slides onto the board at the front of the room and read them to the students. Each slide presented either a multiple choice question or a statement of fact. When the slide contained a question, students used clickers (handheld, cell-phone-like remotes) to indicate their answer choice: A, B, C, or D. When all had responded, the correct answer was revealed, so as to provide feedback and correct errors. (Although teachers were not present for the quizzes, under normal circumstances, with teachers administrating the quizzes they would see immediately how well the students were tracking the study material and use the results to guide further discussion or study. ...they had been quizzed three times on one third of the material, and they had seen another third presented for additional study three times." "The results were compelling: The kids scored a full grade higher on the material that had been quizzed than on the the material that had not been quizzed. Moreover, test results for the material that had been reviewed as statements of fact but not quizzed were no better than those for the non reviewed material." "In 2007, the research was extended to eighth grade science classes, covering genetics, evolution and anatomy. The regimen was the same, and the results equally impressive. At the end of three semesters, the eighth graders averaged 79 percent (C+) on the science material that had not been quizzed, compared to 92 percent (A-) on the material that had been quizzed. The

testing effect persisted eight months later at the

end of year exams, confirming what many laboratory

studies have shown about the long-term benefits of

retrieval practice. The effect doubtless would have

been greater if retrieval practice had continued and

occurred once a month in the intervening

months." Read

test, lecture test. So why don't we test

students after each reading or lecture? The main

reason is that it would be an enormous job for

teachers to grade all those tests. But since the

reason for the test is not to grade but rather to

force the students to recall the information, there is

actually no need to grade the test at all. The teacher

could simply put all the test answers up afterward or

simply go through the test and give each answer an

explanation. Also the answers would not have to be in

the form of box ticking and could require students to

answer the questions in their own words. If we wanted

to be sure all the students were trying to recall we

could have the tests checked by other students. They

could hand their paper to the person beside the or the

person in front or behind. This sort of thing has been

done in many schools successfully but is not the norm

in any country as far this site is aware. The point is

that the main problem with testing is grading and

stakes as will be made clear below.

No stakes testing. All the testing carried out at the Columbia middle school carried no stakes and yet were very effective. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel put it like this: "These

quizzes were for 'no stakes' meaning that the scores

were not counted toward a grade." The best kind of study. If you are going to study for a single test the best kind of study is to have two students working together where one tests the other and they then change places and the other is tested. What also works is to reread a sentence of text then try and recall the whole paragraph with the book closed then read it to see what you got right and wrong. As they say above a simple test after each reading or lecture would work far better as far as work load goes. Incentive. It may well be that ungraded tests would be highly effective in practicing retrieval if students were willing participants in it. However, if there was no grading it may be thought by some that students would be unwilling to actually try to recall specific information as they would have little incentive to try. Teachers who are of this opinion can overcome this idea by having students give their answers verbally to the rest of the class. This would certainly provide an incentive to try. Another way to solve this problem is to have each students answers checked by another class member. Another way to avoid grading might be to have the students type the answers in to a computer program that could tell if the answer was right or wrong and inform the student and if need be the teacher. The effectiveness of different types of testing as retrieval practice. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel put it like this: "Tests that require the learner to supply the answer, like an essay or short-answer test, or simply practice with flash cards, appear to be more effective than simple recognition tests like multiple choice or true/false tests. However, even multiple choice tests like those used at Columbia Middle School can yield strong benefits. While any kind of retrieval practice generally benefits learning, the implication seems to be that where more cognitive effort is required for retrieval, greater retention results." [Or less forgetting occurs. The implication is that retrieval interrupts the forgetting of the material that is retrieved.] The motivational effects of low stakes testing. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain: "After a test, students spend more time restudying the material they they missed. and they learn more from it than do their peers who restudy the material without being tested. Students who's study strategies emphasize rereading but not self-testing show over confidence in their mastery. Students who have been quizzed have a double advantage over those who have not: a more accurate sense of of what they know and the strengthening of learning that accrues fro retrieval practice." What should be our take away about retrieval practice? Here is what Brown, Roediger and McDaniel say: "Repeated retrieval not only makes memories more durable but produces knowledge that can be retrieved more readily, in more varied settings, and applied to a wider variety of problems."

"An apt analogy for how the brain consolidates new learning may be the experience of composing an essay. The first draft is rangy, imprecise. You discover what you want to say by trying to write it. After a couple of revisions you have sharpened the piece and cut away some of the extraneous points. You put it aside to let it ferment. When you pick it up again a day or two later, what you want to say has become clearer in your mind. Perhaps you now perceive that there are three main points you are making. You connect them to examples and supporting information familiar to your audience. You rearrange and draw together the elements of your argument to make it more effective and elegant. Similarly,

the process of learning something often starts out

feeling disorganized and unwieldy; the most

important aspects are not always salient.

Consolidation helps organize and solidify learning

and, notably, so does retrieval after a lapse of

some time, because the act of retrieving a memory

from long-term storage can both strengthen the

memory traces and at the same time make them

modifiable again, enabling them, for example to

connect to more recent learning. This process is

called reconsolidation. This is how retrieval

practice modifies and strengthens learning."

NO STAKES AND LOW STAKES TESTS USAGE. If non graded tests can

be used to improve the retrieval of specific stored

memories, and this site holds that it can, it becomes

necessary to consider how this mechanism could be used

to do just that; to improve activation for the

retrieval of specific memories. Here are some

possibilities:

Spaced intervals. We have long known that relearning or studying has to be scheduled in a way that does not occupy all our time and yet somehow manages to keep memories in tact. The earliest efforts to investigate this trade off used fixed, spaced intervals. Although many of the investigations concerning spacing out study times were conducted before attention was focused on retrieval practice it turns out that spacing out any kind of study or retrieval practice works much the same way as in using flash cards.  Expanding intervals. A number of studies have now been done that clearly show how intervals can be used to make memory more efficient by interrupting forgetting. One of the first solid looks at spacing was done by a 19 year old Polish college student Piotr Wozniak who was trying to learn English. He had lots of other classes taking up his time but he needed a larger English vocabulary to be proficient in all of them. In his book "How We Learn" Benedict Cary presents the following information about Wosniak: "He found that, after a single study session, he could recall a new word for a couple of days. But if he restudied on the next day the word was retrievable for about a week. After a third review session, a week after the second, the word was retrievable for nearly a month. Wosniak himself wrote: "Intervals should be as long as possible to obtain the minimum frequency of repetitions, and to make the best of the so-called spacing effect...Intervals should be short enough to ensure that the knowledge is still remembered." Cary continues: "Before long, Wosniak was living and learning according to the rhythms of his system..." The English experiment became an algorithm, then a personal mission, and finally, in 1987, he turned it into a software package called Super-Memo. Super-Memo teaches according to Wosniak's calculations. It provides digital flash cards and a daily calendar for study, keeping track of when words were first studied and representing them according to the spacing effect. Each previously studied word pops up on screen just before that word is about to drop out of reach of retrieval." This app is easy to use and free. Although apps do not exist for all subjects anyone can do calculations with chunks of data to find optimal study intervals. They always work out to be intervals that are ever expanding. Many studies have been done by both scientists and teachers showing this to be workable for any subject. Trying to retain learning for a lifetime. In 1993 the Four Bahricks Study appeared. If Wosniak had established minimum intervals for learning the Bahrick family established the maximum learning intervals for lifetime learning. This kind of learning dealt with lists of words many of which would go past the possibility of retrieval. But being relearned after being forgotten was still effective,especially as they made a conscious effort to find new cues for the words greatly increasing the elaboration of each word memory. In his book "How We Learn" Benedict Cary says: "After five years the family scored highest on the list they'd reviewed according to the most widely spaced, the longest running schedule: once every two months for twenty-six sessions." The Bahrick's study used fixed space intervals in their schedule, but it seems likely that this type of relearning would also benefit from intervals that are ever expanding in length rather than of fixed length. Why is spaced retrieval practice more effective than massed retrieval practice? In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain: "Why is spaced practice more effective than massed practice? It appears that embedding new learning in long term memory requires a process of consolidation, in which memory traces (the brain's representations of the new learning) are strengthened, given meaning and connected to prior knowledge - a process that unfolds over hours, and may take several days. Rapid fire practice leans on short-term memory. Durable learning, however, requires time for mental rehearsal and the processes of consolidation. Hence, spaced practice works better." Increasing time till forgetting. Think of it as like many many connections being forged each time we embed a memory in long-term storage. If after some time that memory is not used (retrieved) then it is pruned away by the mechanism of forgetting. When we retrieve that memory, the mechanism that trims away memories that have not been used, is interrupted and the memory is re-consolidated back into long-term memory but with an increased lifespan. With every recall of a memory its lifespan is increased greatly and thus the period to when it will next be forgotten may expand many times over.  Preclusion of consolidation and re-consolidation. Some memories take a lot of time to consolidate or re-consolidate. It probably depends on how many connection they have to make with prior knowledge. If we mass practice and space the practice times too close together we may be preventing the initial consolidation and or subsequent re-consolidation from taking place at all. (Consolidation or re-consolidation may take hours or even days to complete.) Our brains may start to consolidate a new memory but will be interrupted and have to start again with a slightly different memory. In this way no benefit may be obtained from the repetition at all. How much time should we allow between memory retrievals? This is a good question and the answer may not seem very helpful at first. In fact the answer was found by Wosniak in his discovery. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain: "How much time [do you put between each retrieval]? It depends on the material. If you are learning a set of names and faces, you will need review them within a few minutes of your first encounter, because these associations are forgotten quickly. New material in a text may need to be retrieved within a day or so of your first encounter with it. Then, perhaps not again for several days or a week. When you are feeling more sure of your mastery of certain material, quiz yourself on it once a month." "Sleep

seems to play a large role in memory consolidation,

so practice with at least a day in between sessions

is good." You have to build your own schedule. The point is that every person will differ in how long things take before they begin to be forgotten and that every domain, material or type of learning will also be different in how long it takes forgetting to take place. This makes things difficult but not impossible. This was the same problem that faced Wosniak and he solved it so anybody can solve it for themselves. Remember intervals should be as long as possible to obtain the minimum frequency of repetitions, and should be short enough to ensure that the knowledge is still remembered. You simply have to work out each period of forgetting for yourself for each subject. Once you have worked this out for a single item you will find it works just as well for any similar item. You will find like Wosniak that each schedule expands greatly with each retrieval. Although this is bad news for teachers it is only another problem to be solved. Even though a perfect schedule cannot be made to fit a whole class, students will still be greatly helped by any kind of retrieval practice. DESIRABLE

DIFFICULTIES (VARIATION AND INTERLEAVING). Desirably difficult. Elisabeth and Robert Bjork coined the term 'desirable difficulties' to explain why more difficult types of practice tend to work better in both developing a skill and in the formation of long term memories. Desirable difficulties is perhaps best exemplified by a corollary of the old adage that what you do not use you lose. This could be expressed as, the more difficult an action is, while remaining achievable, the more likely it is to improve our health and physicality. (Difficult exercise that does not strain us makes us healthy and physically stronger.) It is not surprising that this is similarly true of the brain or such things as memory traces.

"Think of a baseball batter waiting for the pitch. He has less than an instant to decipher whether its a curveball, a changeup or something else. How does he do it? There a few subtle signals that help: the way the pitcher winds up, the way he throws, the spin of the ball's seams. A great batter winnows out all the extraneous perceptual distractions, seeing only those variations in the pitches, and through practice he forms distinct mental models based on on a different set of cues for each kind of pitch. He connect these models to what he knows about the batting stance, strike zone and swinging so as to stay on top of the ball. These he connects to mental models of player positions: if he's got guys on first and second, maybe he'll sacrifice to move the runners ahead. If he's got men on first and there is one out, he's got to from hitting into a double play while still hitting to score the runner. His mental models of player positions connect to his models of the opposition (are they playing deep or shallow?) and to the signals flying around from the dugout to the base coaches to him. In a great at-bat, all these pieces come together seamlessly: the batter connects with the ball and drives it through a hole in the outfield, buying time to get on first and advance his men. Because he has culled out all but the most important elements for identifying and responding to each kind of pitch, constructed mental models out of that learning, and connected those models to his mastery of the other essential elements of this complex game, an expert player has a better chance of scoring runs than a less experienced one who cannot make sense of the vast and changeable information he faces every time he steps up to the plate." [More on mental models or mental representations later.]

Many

cues for one memory. What we need when trying

to recall something from memory is not like with a

skill. With a skill each cue activates a slightly

different action. But when trying to retrieve a memory

we need many cues that will activate a single memory

and they can double up to retrieve other memories as

well unless discrimination needs to be involved.

"Researchers

initially predicted that massed practice in

identifying painters works (that is, studying many

examples of one painter's works before moving on to

study many examples of another's works) would best

help students learn the defining characteristics of

each artists style. Massed practice of each artists

work, one artist at a time, would better enable

students to match artworks to artists later,

compared to interleaved exposure to the works of

different artists. The idea was that interleaving

would be too hard and confusing; students would

never be able to sort out the the relevant

dimensions. The researchers were wrong. The

commonalities among one painter's works that

students learned through massed practice proved less

useful than the differences between the works of

multiple painters that students learned through

interleaving. Interleaving enabled better

discrimination and produced better scores on a later

test that required matching the works with their

painters. The interleaving group was also better

able to match painters' names correctly to new

examples of their work that the group had never

viewed during the the learning phase."

Real world practice is interleaving. When we use interleaving in our retrieval practice we are doing it the way it will come to us in the real world. When we get a test everything will be mixed up when we are performing a skill it is not going to play out in a nice orderly fashion. We need to know when and where to act and which motor skill to activate. We need to be ready to perform in real world settings where you can discern a context that requires a specific type of action and then activates that action.

Interleaving and variation are cue formation. Interleaving works because when we just recall the same memory over and over our attention is not on what makes the context in which the memory occurs different from another similar context. In fact we are instead focused on the memory it self. But when what is needed to be recalled is not completely unique in itself or it is part of a group of very similar contexts then we may need to be able to distinguish between hundreds of contextual differences. Each of those contextual differences has to be formed into a cue that will activate the correct corresponding motor program or the retrieval of the correct corresponding memory. Similarly if we switch from one activity to an entirely different activity and then switch back we are forced to notice and create cues to differentiate the two contexts. Similarly if we mix up many different activities at first it will be difficult to perform each action correctly but the whole point in doing this is to create ques for when it is appropriate to activate each motor program. Variation is a form of interleaving with minor differences whereas other interleaving might mix actions that have no connection. But the reason they work is the same. In both cases we are learning when one is appropriate for use. We are creating and distinguishing different cues for each action. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel put it like this: "If you are trying to learn mathematical formulas, study more than one type at a time, so that you are alternating between different problems that call for different solutions If you are studying biology specimens, Dutch painters, or macroeconomics, mix up the examples." "When you structure your study regimen, once you reach the point where you understand a new problem type and its solution but your grasp of it is still rudimentary, scatter this problem type throughout your practice sequence so that you are alternately quizzing yourself on various problem types and retrieving the appropriate solutions for each." Sport and interleaving. Interleaved sporting practice works similarly but a bit different because of more complexity as Brown, Roediger and McDaniel point out: "In interleaving you don't move from a complete practice set of one topic to go to another. You switch before each practice is complete. A friend of ours describes his own experience with this: 'I go to hockey class and were learning skating, puck handling, shooting, and I notice that I get frustrated because we do a little bit of skating and just when I think I'm getting it, we go to stick handling, and I go home frustrated saying, 'Why doesn't this guy keep letting us do these thing until we get it?'' This is actually a rare coach who understands that its more effective to distribute practice across these different skills than polish each one in turn. The athlete is frustrated because the learning's not proceeding quickly, but the next time he will be better at all aspects, the skating the stick handling, and so on, than if he'd dedicated each session to polishing one skill." No re-consolidation. Massed practice has another problem in that the turnaround in practice may be so short that we may be retrieving the memory from working memory rather than long term memory. It is only when a memory is retrieved from long term memory that it achieves a labile form where it can easily altered. A memory pulled from working memory may not have any new links forged and so may not be altered in any way despite improvement in the moment. Blocked practice. Blocked practice is used in sports especially team sports. These are are very complicated maneuvers often requiring the interactions of many players. They are difficult to get right because they have many moving parts so it is not surprising that players and coaches want to keep working at them repeating over and over until they get them right. They are difficult enough to get right once let alone how confusing they become if interleaved with other maneuvers. However, this type of massed practice gives a false appearance of progress, but is of little use in producing effective skills or long term retentiveness. Brown, Roediger and McDaniel have this to say: "How it feels. Blocked practice - that is, mastering all of one type of problem before progressing to another practice type - feels (and looks) like you're getting better mastery as you go, whereas interrupting the study of one type to practice with a different type feels disruptive and counterproductive. Even when learners achieve superior mastery from interleaved practice, they persist in feeling that blocked practice serves them better. You may also experience this feeling, but you now have the advantage of knowing that studies show that this feeling is illusory." "...the interleaved strategy, which was more difficult and felt clunky, produced superior discrimination of differences between types, without hindering the ability to learn commonalities within a type." Brown, Roediger and McDaniel also noticed an increased sensitivity to both differences and similarities when learners uses retrieval interleaving of two or more sorts of material. They say: "It's

thought that this heightened sensitivity to

similarities and differences during interleaving

practice leads to the encoding of more complex and

nuanced representations of the study material - a

better understanding of how specimens or types of

problems are distinctive and why they call for for a

different interpretation or solution."

Spacing, interleaving and variability reflect reality. Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain: "Spacing, interleaving and variability are natural features of how we conduct our lives. Every patient visit or football game is a test and an exercise in in retrieval practice. Every routine traffic stop is a test for a cop. And every traffic stop is different, adding to a cop's explicit and implicit memory and, if she pays attention, making her more effective in the future. The common term is 'learning from experience.'" Natural tools. It is not surprising then that spacing, interleaving and variability work so well when we study using retrieval practice. This mixed up spaced out retrieval is how we encounter the necessity for retrieval in our everyday reality. By reflecting the circumstances in which recall is normally required these tools must to be seen as natural. Blocked or massed practice, on the other hand, must be seen as unnatural. Mixing

the unmixable. When we mix up questions when

retrieving material for a test this helps us to

distinguish one type of question from another as we

will encounter them mixed up in a test or in real life

encounters. It helps us create a cue that will

activate the correct answer. But what if we interleave

retrieval in two different domains such as maths

questions with English questions. Two things. One we

do not need to distinguish maths questions from

English questions because the are obviously different.

Two maths questions and English question will never

appear on the same exam so there is no need to

distinguish them. Not only that but they will hardly

ever appear in conjunction in real world conditions.

So, is there no benefit from interleaving these

questions? While there is no direct benefit in

distinguishing these very unalike retrievals there are

benefits. There are general real world benefits. They

still prepare us for the unpredictable way questions

will eventually turn up in the real world. Also they

are still allowing us to stretch our intervals between

retrievals and yet retrieve other information in

between. Not all difficulties are desirable. Anxiety caused by fear of making mistakes, failure and the inability to overcome obstacles is one such difficulty. Other difficulties that are not desirable are mostly obvious as Brown, Roediger and McDaniel explain in the following: "Outlining

a lesson in a sequence different from the one in the

textbook is not a desirable difficulty for learners

who lack the reading skills or language fluency

required to hold a train of thought long enough to

reconcile the discrepancy. If your textbook is

written in Lithuanian and you don't know the

language, this hardly represents a desirable

difficulty. To be desirable a difficulty must be

something learners can overcome through increased

effort. Intuitively

it makes sense that difficulties that don't

strengthen the skills you will need, or the kinds of

challenges you are likely to encounter in in the

real-world application of you learning, are not

desirable. Having somebody whisper in your ear while

you read the news may be essential training for a TV

anchor. Being, heckled by role-playing protesters

while honing your campaign speech may help train up

a politician. But neither of these difficulties is

likely to be helpful for Rotary Club presidents or

aspiring You Tube bloggers who want to improve their

stage presence." Evidence for desirable difficulties. Other discoveries that indicate the effectiveness of spacing and interleaving may be because of the desirability of difficulties are as follows.

USES

OF RETRIEVAL, INTERVAL SPACING AND INTERLEAVING. Many of the ways retrieval, interval spacing and interleaving are used come together in a single technique. So they are presented here.  USES FOR LEARNERS. There are many things a learner can do to increase the possibility of memory permanence. Here are a few.

USES FOR TEACHERS. There are many things a teacher can do to try and ensure that students retrieve as much as possible of their subject matter as often as is necessary to make likely the possibility of memory permanence. Most of these following ideas come from the books "Make it Stick" and "Powerful Teaching". Here are a few ways in which this can be done:

Obviously students should be asked to check what they have written against the textbook when the class is finishing and clarified with the teacher if something is not understood.

Pretest test. Surprisingly testing and retrieval practice work whether the learner has any relevant knowledge to recall or not. When a learner is presented with a problem rather than a solution the learner's brain grapples with the problem despite the learners lack of sufficient knowledge. By doing so it prepares the brain of the learner for the eventual answers. The questions are embed in the learner's brain as they try to answer questions with metaphorical blank spaces left for the answers.  Whether

the learner happens to find an answer with out the

knowledge to do so or not, this process is called

generation and is a form of creativity. But whether

the learner produces an answer or not the outcome will

be that the answer, when it comes, will be retrieved

more easily and will remain in memory for a longer

period. When the learner has to wait to be given an

answer the process is called priming because the

unanswered questions impel their brain to continue

looking for the answer. It is where the brain is made

receptive by the nagging questions. Priming is simply

preparing a situation where one outcome is more likely

than another. Priming the brain to be receptive. Brown, Roediger and McDaniel also draw our attention to the fact that our brains can be primed to be receptive to various types of knowledge by being tested on subject matter before it is imparted to us as follows: "When you're asked to struggle with a problem before being shown how to solve it, the subsequent solution is better learned and more durably remembered. When you've bought a fishing boat and are attempting to to attach an anchor line, you are far more likely to learn and remember a bowline knot than when you're standing in a city park being shown the bow line by a boy scout..." In both instances our brains are made receptive to the particular information needed making the eventual consolidation more connective and the memory more durable. High-order learning (creation and priming). Brown, Roediger and McDaniel continue: "In testing, being required to supply an answer rather than select from multiple choice options often provides stronger learning benefits. Having to write a short essay makes them stronger still. Overcoming these mild difficulties is a form of active learning, where students engage in higher-order thinking tasks rather than passively receiving knowledge conferred by others." "When you're asked to supply an answer or a solution to something that's new to you, the power of generation to aid learning is even more evident. One explanation for this effect is the idea that as you cast about for a solution, retrieving related knowledge from memory, strengthen the route to a gap in your learning even before the answer is provided to fill it, connections are made to the related material that is fresh in your mind from the effort. [These new strengthened connections could also provide easier and stronger connections with prior knowledge as in elaboration.] Even if you're unsure, thinking about alternatives before you hit on (or are given) the correct answer will help you." "Wrestling with the question, you rack you brain for something that might give you an idea. You may get curious, even stumped or frustrated and acutely aware of the hole in your knowledge that needs filling. When you are then shown the solution a light goes on. Unsuccessful attempts to solve a problem encourage deep processing of the answers when it is later supplied, creating fertile ground for its encoding, in a way that simply reading the answer cannot. It's better to solve a problem than to memorize a solution. It's better to attempt a solution and supply the incorrect answer than not to make the attempt." USES

FOR TEACHERS. This kind of test that precedes actual learning was found by Pooja Agarwal in a study to extend to extend the life of memories and to do so significantly when combined with other retrieval practice occurring just after learning and again two days later. It may have limited value by itself. While teachers might not want to take up too much teaching time with it a quick quiz at the beginning of each lesson may extend the time to forgetting significantly when supported by other tests. This should take the form of questions about the main concepts, points and ideas that you are going to teach in the lesson and should be supported by other tests (retrieval practice) after learning to ensure its potential.

Feedback enables improvement in two ways. Feedback enables us to see where we have gone right so we can repeat it again and move closer to making the action automatic and it also shows where we have gone wrong so we can correct the action and thus make some improvement in the action. But feedback is not always good so it is essential to define what makes good feedback. Some

people believe that feedback is meant to enable us to

find where our actions are weakest and then try to

improve those areas by being given feedback that sets

out how to do so. This means that feedback would be

mostly criticism. This works fine when learners are

already highly motivated but does not work well when

learners are not motivated. This site holds that it is

necessary to not only have positive feedback as well

but to continue to improve what you are already doing

well and never really let most learned actions become

completely automatic.

Corrective

improvement. Sometimes this may be just about

where a learner may have forgotten information or lost

access to it. In this case the learner is guided by

the feedback to relearn the information in question.

Sometimes it may be about finding areas in which your

memories are fading or are just weak so it can guide

the learner to focus on those areas. But mostly it is

about doing what has not been well and improving it,

by implementing a superior model/template we have seen

or has been conveyed to us by a coach or mentor. Creative

improvement. But at other times feedback can

reveal weaknesses or flaws in the actual knowledge

content of the memory itself. This may present itself

in the form of a problem to be solved. Feedback can

thus point out this problem to be solved causing a

previous action or work to be scrutinized and varied

creatively to improve the action or work. Such new

variants can then be tested in reality. Sometimes some

new incoming information may help stitch the old

previous knowledge together in a new way and sometimes

the seeds of new information are already there lost in

the expanse of prior knowledge. In this way feedback

can prompt something really new and unique to emerge

as a creative improvement on what has gone before. Two forms of feedback.

Self feedback and creativity. Reflection is a form of recall but it is also a form of, or condition for, self feedback. Reflection is something we tend to do after we make a mistake. We recall an incident, we often construct a mental model of what happened and then we start building variants of that incident to examine what we could have done differently. Sometimes we do this to find any errors we may have made and thus correct them so we do not make them next time. But sometimes by creating these variant actions we can come up with a totally new way of doing something that did not exist before we thought of it. We solve a problem or create a uniquely new solution. We recall a mistake from memory and vary it till we find something that works in an act of creation. Feed back is only as good as the person giving it. We should therefore try to be sure about a mentor's credentials, but we should also be as sure as possible of our own lack of credentials. There are actually many reasons why we might get bad feedback from ourselves. (1) The desire for narrative cohesion in the events of our lives. One reason is that humans desire for the world to make sense. We want to know why and how things happen, we want to know what causes things. While this might seem to be a good thing it can be and is abused. This happens when we don't know something but just make something up to keep this desire happy. Sometimes this results in our adding in small elements to our memories to help the memories to make more sense, and sometimes it can be a group thing where a society evolves a myth that makes the world more understandable. We desire stories that are narratively consonant. (2) Stupid people lack the knowledge that they are stupid. It has long been known that most people tend to be sure that they are right and that they are doing things correctly. In other words we think that we have much more knowledge than we do. One of the main reasons why this is so, is that when we have just heard something or just read it or just seen it, we will tend to think that we know it well and will always remember it.

This is because we are currently experiencing what is in our working memory which seems to be connected to a host of recently retrieved memories which seem easily accessible. This kind of illusion of knowing more than we do is called the illusion of fluency.

The Dunning Kruger effect. Memories take a long time to become permanently embedded in long term memory and often require many many retrievals before they become fully embedded. What we often experience is an illusion of fluency in subjects we believe we have learned. We may have learned them and forgotten them. We may have learned them incorrectly or we may have never learned them and merely believe that we have learned them.

We have ways of overcoming this tendency to

overestimate our own knowledge. We do this by

listening to feedback from others and testing our own

knowledge against texts or scientifically. Not

surprisingly the smarter we are the better we will

probably be at doing this. This being true means that

stupid people will generally think they know much more

than they do. This is called the Dunning Kruger effect

after the people who first noticed the effect. The

ability to overcome this flaw in our own feedback is

called meta cognition.

Feedback pitfalls. Feedback when provided by a coach, a mentor or a teacher while essential to good early learning has a number of pitfalls. The teacher, coach or mentor may be lacking in the most up-to-date teaching or learning techniques even if he/she is an expert. The teacher, coach or mentor may be lacking the skills needed to impart good learning techniques to the learner despite being an expert in the subject matter. More can be found on giving good negative feedback on the criticism page and positive feedback on the self-theories page. Also there is what is called the curse of knowledge.

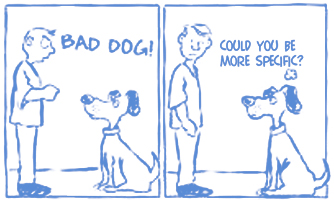

The curse

of knowledge. The curse of knowledge the

inability of experts to explain information in ways

that are understandable to lesser informed

individuals. This is because it is difficult for

anyone to imagine not knowing something that they know

or what their mind was like before they knew it. In

this way exerts can get lost in what they know unable

to pass it on or be able to give good feedback. This

can lead to all sorts of communication problems.

Sometimes this can lead to feedback lacking

specificity where important information is left out

because it is assumed it is known. Jargon words may be

used that learners do not know. At other times the

coach or trainer can assume the learner is not

understanding because they are hard of hearing and

respond by raising their voice.

Blaming the learner. It is very easy for a teacher or coach to blame the learners for his/her own inability to make feedback or any information understandable. Coaches etc. must try to avoid this curse whether presenting models or giving feedback and not blame the learner for their inability like Dilbert below.  Too much, too different, too complex. Coaches should be aware that their feedback, like their modeling, can suffer from the curse of knowledge. It is easy to give too much feedback, feedback for which the learner has no frame of reference, or feedback that is too complex. Just because an expert knows how to do something well does not mean he/she knows how to pass that information on to learners in a form they can understand and comply with. Indeed experts can both assume learners can understand what they say and yet lose patients with them when they fail to understand. Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi give this humorous example of tennis super coach a learner might have hired to lift their game: "I am going to tell you one more time...There are nine things you must do to hit a forehand. Only nine." The learner tries and fails again and again. He gets one thing right but forgets most of the others. The learner is not even able to keep all nine ideas in memory despite being told them over and over. Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi continue: "Turns out...knowledge can get in the way of learning when it isn't doled out in manageable pieces. This is Super Coach's problem: asking you to pay attention to nine things at once is all but impossible. But he is not alone; most people - the three of us included are inclined to give too much feedback at once." "One of the keys to coaching, then is to develop the self discipline to focus on fewer things" Limit information. The coach has to somehow limit the amount of information he/she gives,and limit the complexity of information in every feedback delivery.Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi continue: "When performers or employees or team members or children are trying to concentrate on more than one or two specific things at once, attention becomes fractured and diluted. Ironically this can result in reduced performance."

Start with what is known. A coach must also put himself or herself in the learners shoes to understand what the learner knows, and build from that. Any learning must connect to what the learner knows, in order to provide context for the learner's understanding. Consistency. Not only that but the coach has to make sure each feedback delivery is consistent with all the other feedback deliveries and contain no inconsistencies. SHORTEN THE FEEDBACK LOOP. Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi understand that feedback is believed to be most effective if it is given quickly and if it is acted on quickly. They say: "With feedback, it turns out that speed is critically important - maybe the single most important factor in determining its success." "John Wooden was notoriously obsessive about this. As one of his players wrote, 'He believed correction was wasted unless done immediately.' As the minutes slipped by, the player's mind and body would forget the situation. Once he had practiced doing it wrong, the window rapidly snapped shut and correction becomes useless."

Lemov, Woolway and Yezzi give a good example of how to do loop shortening as follows: "Katie's shortened the feedback twice. She cut off the exercise and gave the teacher feedback right away, as soon as he began to struggle, and sent him back to the beginning so he would practice using the feedback. But even before that she asked him to rehearse in his head. There were just a few short seconds between when he began to founder and when she was there to support and just a few seconds before he started to apply the feedback. The teacher did as Katie asked, even though he was nervous and perhaps not really sold on the feedback." "...the memory of the failure was truncated and instantly replaced by success... The teacher used the technique for a minute and was visibly pleased and happy..." Feedback delay. Just recently it has been found that a slight delay in feedback actually produces better memory results than does immediate feedback. There are several reasons why this might be so. Firstly if the feedback is too quick it may not involve any recall as the information may be retrieved from working memory where what we are concerned about right now is temporally stored. In other words the two variant actions go into long term memory simultaneously with no preference given to either thus the end result may end up being a mixture of both rather than two separate iterations. Also the lack of actual recall may mean that the memory retains a rigid form rather than the labile form of a memory that occurs during recall. Thus performing the feedback and re-performance too quickly may prevent any re-consolidation from taking place. The delay should obviously not be so long that another performance occurs before the the feedback is given but rather only enough time for the knowledge to leave working memory. Error-less learning. It should also be noted that in no way should the idea of error less learning be considered when giving feedback. In their book "Make it Stick" Brown, Roediger and McDaniel point out the following: "In the 1950s and 19650s the psychologist B. F. Skinner advocated the adoption of 'errorless learning' methods in education in the belief that errors by learners are counter productive and result from faulty instruction." This led to an unfortunate form of teaching where learners were spoon fed tiny amounts of new material with such instant feedback that it was virtually impossible to make a mistake. This type of learning has been called error-less learning which has proved to produce quick forgetting and little consolidation in long term memory despite producing such seemingly perfect initial results.

When we

are learning anything we have to assess the new

against the past. With actions we have to be able to

assess if the new variant action we have produced is

superior to the action that preceded its creation. If

we have a coach or teacher they can provide us with

feedback about what we are doing wrong and when we

have done it right. We also have media to provide

feedback. However, in the end it is our own ability to

discriminate, what we are doing wrong and when we have

done something right, that is the most critical factor

in improving our skill. To do this effectively we need

to be able to build accurate mental

representations.  Elsewhere on this site reality patterns are talked about. These are one form of mental representation. They are the mental representations with which we build to understand reality. They are models of or aspects of external reality and they in turn come together to produce a map of reality and how it works. It is the glue that holds together our knowledge, connects our knowledge and makes reality understandable. But mental representations may come in other forms as well. With the learning of actions and the building of them into skills another sort of mental representation may be necessary. These are the representation of actions themselves and how we feel when we perform those actions. In his book "Peak" Anders Ericsson puts it like this: "Even when the skill being practiced is primarily physical, a major factor is the development of the proper mental representations. Consider a competitive diver working on a new dive. Much of the practice is devoted to forming a clear mental picture of what the dive should look like at every moment and, more importantly, what it should feel like in terms of body positioning and momentum.

Of course, the deliberate practice will also lead to physical changes in the body itself - in divers, the development of the legs, abdominal muscles, back, and shoulders among other body parts - but without the mental representations necessary to produce and control the body's movements correctly, the physical changes would be of no use."  The two important functions of feedback. Feedback has two important functions and mental representations are a necessary part of both of those functions.

Mirror neurons. In any case the action part of any mental representation seems likely to take place in what are being called mirror neurons. These are specialized neurons (in our brains) that seem to be there to enable us to imitate others. When we see an action taking place, imagine performing an action, or even think about an action, these special neurons light up like Christmas lights. It seems very likely then, that our first attempts at performing an action come from these neurons. We see an action performed and wish to duplicate it ourselves. We try and probably fail. But this provides the first mental representation of the action.

Great Thinkers and grading. It is perhaps pertinent, to point out here, that many of the world's great thinkers had difficulty at school, and were often unable to pass exams necessary to move them to what we would consider to be their true station in life. These are the people who expand the frontier of knowledge and there is a slight possibility exams can prevent such people making their unique contribution. Let us consider the lives of two of these great thinkers, Albert Einstein and Evariste Galois. Einstein was chosen because everybody knows him. Einstein is so iconic that his name has become synonymous with genius. Only Leonardo Da Vinci could have claimed such a thing previously. It is interesting to note, therefore, that Einstein was not very good with some school work and had little patience with exams and tests. This was so much so, that he had to start his working life as a patent clerk and not as a working scientist. Einstein of course, became famous after some of his important scientific papers had been published. However, such is not the case with Galois. He never achieved fame or any position of importance nor were many of his peers even aware of his work. Yet he was arguably the greatest mathematician of all time. Galois' story is a cautionary tale for those who think exams are important. He was failed over and over again and was never granted entrance to the kind of college that could have promoted his work. His work was set aside and lost. He was not able to mix with his peers and most of his work was never published while he was alive. Most of what we know of his work, comes from frantic scribblings on the eve of a stupid duel, where he was fatally wounded in his twenty first year of life. We have many reasons for rejecting tests, not the least of which may be that they are time wasting and even damaging to learning. The damage that testing and exams can do was probably best expressed by Jean Piaget in "To Understand is to Invent" as follows.

Although there are many other things wrong with tests, the single most damaging thing about tests is the fact that they are graded. It is grading that sets us apart from one another. It is grading that tells us that some of us are better or worse than others and by how much. It raises the stakes. As motivation goes this means that the higher rated may be motivated to continue, while the lower rated will not, and may in fact, be motivated not to try. The real problem with grades, however, is that it moves children away from learning what they are interested in, in favor of working at that which will get them the best grades.    There are many criticisms of grading but people who are interested to learn more about the harm grades and grading can do are advised to read "Wad-Ja-Get?" by Kirschenbaum Simon and Napier. This book shows how grading encourages cheating, brown nosing or grade grubbing. It shows how teachers are unable to give consistent marks, even when given the same paper only months later, and how the variation with a different teacher grading the same paper can be as much as 25%. This book is fully supported with scientific studies conduced by a wide range of institutions. It also provides thought provoking arguments. Here are some sample excerpts from that book.

Examinations are not really needed for the colleges and universities that should have their own entrance qualifications, including exams if they wish. If colleges wish to determine if students are clever enough or creative enough to be worthy of being selected for their college they could set their own entrance exams, and of course the SATs in America already perform just this function. But then why do the colleges need to determine if someone is good enough to go there? Surely wanting to go there should be enough, and if the school isn't big enough then build it bigger as you would a business. In the end the only exams that nearly everybody agrees make any sort of sense are the college and university degrees. But what are degrees used for? In the end it seems, that exams are useful only for businesses looking for new workers and the acceptance that one is qualified in a profession such as a doctor. Also as Calvin points out much of what students get right on an exam is soon forgotten because it is only retrieved in preparation just before the exam.  Business and professional standards. But is this so? Surely businesses and professions would also be far better off in devising their own entrance exams, rather than relying on exams from other sources like schools, where there are a great variety of standards. For businesses the learning done in school, for the most part, relates to information that is completely irrelevant to their business or profession. So finally we come to entrance exams which still seem to have some claim to being useful in schools. This site suggests, however, that this is mainly a device for keeping out students that the administrators feel would be disruptive or just not of the right sort. While this can not be justified on moral grounds, it is an understandable human prejudice. Certainly teachers get little pleasure from tests. In the current system teachers spend a huge portion of their work time marking, correcting and grading papers. This activity, even more than general paper work, is the single greatest time waster for teachers. For many teachers it is as utterly boring and depressing as it is for the students. If teachers could be freed from this activity, they would have maybe 50% more time to spend actually helping students to learn.

This

results in students passing tests then quickly

forgetting the material. This plus insistence on

students knowing so much that is uninteresting to them

and of little use for them, often leads to teachers,

schools, parents and students all trying to game the

system.  Important.

What is important, is what we do know, what we can

know, and our desire to know it. The effects of evaluation on learning. Although there is still some debate about the scientific effects of high stakes tests, I think it is now generally accepted in scientific circles that high stakes tests and grading generally has a negative effect on learning activities but this may only be because our societies spread and encourage immense anxiety about tests, exams and errors and does not honor the essential or necessary learning involved in how to learn from mistakes, overcome difficulties and recover from failure.

Mark Lepper was the first to suggest that a sense of personal control might be essential motivation and thus to evaluation. Teresa Amabile, Edward Deci, Richard Ryan, Mark Lepper and many others, have gradually through many different and diverse experiments, over a period of about 30 years, pieced together a picture that clearly and scientifically, shows the disastrous effects that evaluation can have on learning. Although nobody seems to have been testing the effects of evaluation specifically on learning, such concepts as creativity studied by Amabile, intrinsic motivation studied by Deci & Ryan, anxiety studies by Moshe Zeidner, cover a wide range of activities including most areas of knowledge that could be called learning.

Edward Deci and Richard Ryan have devised a whole new theory of motivation in an effort to initially explain the detrimental effects that that they found extrinsic rewards to have on intrinsic motivation. "Self-Determination Theory" as their theory is named, addresses the interplay of three basic needs determined as "Autonomy", "Relatedness" and "Competence". Although this theory is less concerned with evaluation as being detrimental to learning and more concerned as to how it can be useful for and in consonance with learning it has produced findings that are very significant. The results of their findings and the results of others such as White which they used as a basis for their theory are presented in their book "Intrinsic Motivation and self-Determination in Human Behavior" as follows:

Deci and Ryan explain: "In so far as people's work is being critically evaluated by an external agent, it is possible that people will lose a sense of self-determination and experience a shift in the perceived locus of causality. Evaluations are the basis for determining whether people are complying with external demands, so evaluations themselves are likely to connote external control and therefore to undermine intrinsic motivation."

Teresa Amabile and her colleagues did studies of the effect of evaluation on creativity. They found their results to be consistent for both children and adults and for both verbal creativity and artistic creativity. The results of their findings in both real world observation and experimental studies from her book "Creativity in Context" are presented here as follows:

Basically what Amabile has discovered through research and experiment is that is that while evaluation is generally detrimental to creativity it can be supportive of creativity if it is work focused and constructive. The single exception to this is those who are unskilled and this Amabile theorizes is because the prospect of negative evaluation co-occurs with low levels of skill. Thus creativity tends to be undermined by evaluation that conveys incompetence or threatens self determination.

Carol Dweck and Andrew Elliot have compiled and edited a compendium on competence called "The Handbook of Competence and Motivation" in which there is an examination of the effects of evaluation on competence by Moshe Zeidner and Gerald Matthews. These studies, although more guarded, also report that test anxiety has some detrimental effects on competence as follows: